Eugene Manuel on 90 Years of Change

At approximately 9:20 p.m. on September 8, 1935, Huey Pierce Long was mortally wounded in the Louisiana State Capitol. Two days later, he would be dead. Ninety years after the death of the Kingfish, he remains one of the most fascinating and controversial figures in American politics. His death marked the end of not only his personal ambitions for the White House but also a distinctive era in Louisiana politics, where local issues shaped the direction of Washington rather than the other way around. Former Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill once said, “All politics is local.” Today, one might say politics was local.

For decades, places like Evangeline Parish were buzzing political hives still in the shadow of Huey Long. Courthouses, school board meetings, and campaign rallies were the heartbeat of local life. “Politics was alive,” recalls Mamou Councilman Eugene Manuel, a French speaker and lifelong Mamou businessman elected in 2022. “It had personality. It had passion. People

didn’t just vote; they argued, they organized, they believed their voices mattered and in many ways their lives directly depended on it.”

Populism, Passion and Patronage

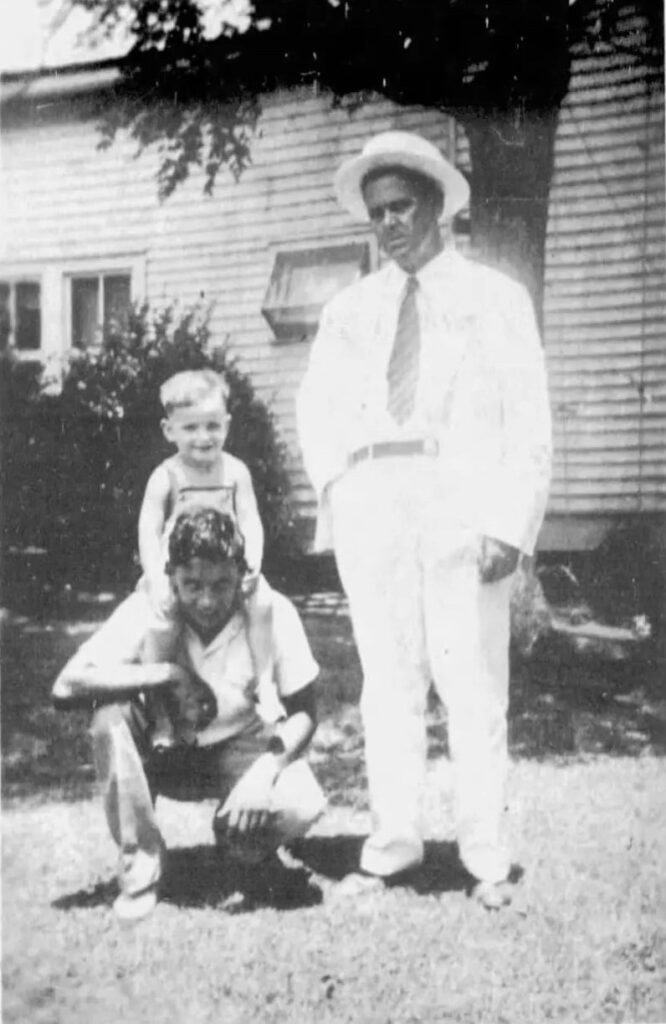

In those years, politics was not an abstract concept—it was survival. Jobs, contracts, and opportunities flowed through from Baton Rouge to parish factions, but not without their own local leadership and ingenuity. Manuel reflects: “I remember my father T. Ed Manuel, Revon Reed, Attorney Paul Tate, Governor Edwin Edwards, Dr. Frank Savoy Sr.; they filled Evangeline Parish with energy and vision in the spirit of Longs’s populism. They fought, they dreamed, but most of all they showed up. That’s the part that’s gone today: people showing up.”

When these men did show up, they brought more than words; they invested their own fiscal and social capital to uplift their town. Voter turnout was high in the populist era, and these doctors, lawyers, farmers, and teachers saw local politics not merely as power, but as a vehicle for the self-actualization of their community. They cultivated rural hospitals, expanded agricultural operations, and sparked a cultural renaissance, all on their own. Their politics was intimate and immediate, grounded in Huey Long’s conviction from Acts 4:32–35 that “the multitude of them that believed were of one heart and of one soul.” To Long, the Acts of the Apostles was a blueprint for his political program. He sought to bring all people together, believing that all were children of God entitled to dignity, equality, and a fair chance at life.

In Evangeline Parish, Dr. Frank Savoy became one of the key translators both politically and literally of Long’s message. As Mayor of Mamou, he bridged the linguistic divide of Cajun country, explaining in plain language what Long promised: better schools, roads, hospitals, and a fairer shake for working people. As Manuel recalled, “Dr. Frank would stand in a crowd after Huey spoke and tell the old folks in French what the man was saying—‘Il veut nous donner une chance,’ he’d say, ‘he wants to give us a chance.’ That’s how people started believing.”.

Huey Long’s rise as a mass leader came from his ability to shun the courthouse gangs and the New Orleans establishment, instead choosing to speak directly to the poor and rural people of Louisiana who had long been left out of politics. This approach nearly succeeded in his first run for governor, though heavy rains flooded rural parishes and kept many of his strongest supporters from reaching the polls.

Even in that narrow 1924 defeat, Long built a loyal following by giving ordinary people a sense of political franchise they had never known before. Four years later, that same movement carried him to victory. Long won the Democratic primary so decisively that his opponent declined to face a runoff, sealing his rise as Louisiana’s first true mass leader.

Long built his reputation as a fearless populist, taking on powerful interests like Standard Oil and repeatedly challenging the political establishment. As Public Service Commissioner and then governor, he faced multiple impeachments and indictments, yet none could stop him from advancing his agenda. His final impeachment in 1929 by the Louisiana House of Representatives

stemmed from his push for a five-cent-per-barrel oil tax to fund his social programs, which angered the state’s special interests. The House impeached him, but the Senate trial collapsed when Long secured a round-robin pledge from 15 senators to vote “not guilty”.

When Long ran for Senate and won in 1930, it was less about Washington and more a referendum on his state programs: infrastructure and education. His career reaffirmed the power of mass leadership and local politics by speaking directly to ordinary people and addressing their immediate needs.

In that era when politics was fundamentally local, language, religion, and regional identity shaped how people saw the world. Long’s genius was to stitch those differences together by meeting, people where they were and offering real solutions to their problems. A “chicken in every pot”, roads, hospitals, textbooks, and LSU expansion brought all people together. His “Share Our Wealth” program electrified millions during the Depression and pushed President Roosevelt to expand the New Deal. Roosevelt himself called Long “the most dangerous man in America” out of fear that through the force of one man, Louisiana would pull Washington into its own orbit.

While Roosevelt’s fear was surely justified, it was quelled when Senator Long was killed and his

movement disintegrated with no one to replace him. Manuel reflected “When Huey died, it was more than the end of his career. It was the start of politics moving away from our courthouses

and Baton Rouge. Slowly but surely, the center shifted. First you had Earl carrying it for a while, but that fire couldn’t burn forever.

Manuel then added, “But when Edwin Edwards did come along, he was like a new Huey Long. He came into Louisiana politics with that spark, igniting the fire again, speaking directly to the

people, promising real solutions, and giving ordinary people a chance.”

In 1972, the Democratic gubernatorial primary was crowded with sixteen candidates. Edwards faced skepticism as a French-speaking Cajun from Crowley but turned that perceived weakness into a massive advantage which catapulted him to the Governor’s mansion four times, connecting with people in a way that made them believe he understood their lives.

“The next generation of Mamou leaders, like Dr. Frank Savoy Jr., carried that same local energy forward with Edwin,” Manuel continued. “They organized votes, translated messages, and made sure people saw themselves in the politics that affected them. Today, that tradition is largely gone. People are hungry for leadership. There is a vacuum.”

From Baton Rouge to Washington

The issues Huey Long championed remain as relevant as ever, yet the strong local leaders are mostly absent. With the insurance crisis, population decline, and inflationary pressures, Louisianans are left to rely on Washington for their political and emotional needs. When there is “no one left to mind the store”, it is left to blight, neglect and unchecked corruption. When the disparity grows between the hand that gives and the hand that takes, the disconnect widens between self-respecting people and the faceless, nameless entities they are made to rely on who neither know nor understand their problems. Though the truth is self-evident, the causes of local political decline are more numerous and nuanced than population exodus alone. It is a cultural, economic and anthropological problem.

In years past, the state’s oil money fueled everything; Long challenged Standard Oil, and Edwards codified it. These governors paid for schools, hospitals, and infrastructure with money pulled straight from the ground in an era when Louisiana politics was self-contained, tied to local resources and driven by local demands.

Under Governor Edwards, severance taxes increased, providing the state a larger portion of oil and gas profits than ever before. The tax structure was modernized, making it more consistent and enforceable, providing reliable revenue for public services. Today, Louisiana has grown increasingly dependent on Washington, D.C. Federal programs now sustain much of what the state government no longer does on its own: healthcare, hurricane relief, infrastructure, and education.

“The center of the universe has shifted,” Manuel said. “When my father was active, everything ran through the governor. Now it all runs through Washington. Baton Rouge used to call the shots; today it takes its cues from D.C.” The ends have not changed—people still seek security, health care, infrastructure, and opportunity. But the means have shifted. Where Long and Edwards once used oil money and state patronage to provide, today poor Louisiana depends on federal programs. Local politics, once the main vehicle for addressing these needs, has withered into a distant secondary role.

Not only have the means changed, but so has its collateral damage. Benjamin Franklin once warned that only an informed public could preserve their system of government, and Louisiana proved the point. When politics drifts from the people it governs, corruption doesn’t disappear, it only grows more distant, more abstract, and more dangerous

Manuel recalled the scandals that followed Huey Long’s death: the so-called Second Louisiana Purchase of the late 1930s. In the midst of the power vacuum Long left behind, the collective wool was pulled over Louisiana’s eyes and the former “Long Machine” was wielded by bad actors for self-enrichment, siphoning federal relief money and rigging state contracts. Governor Richard Leche famously remarked that when he took the oath of office, “I didn’t take a vow of poverty.” He was later convicted of mail fraud while LSU president James Monroe fled to Canada to avoid prosecution for embezzlement.

Corruption near or far

The legacy of Spanish and Franco rule in Louisiana included a tradition of real corruption, it was crooked, but self-contained to the state. To some, Edwin Edwards’s legal woes embodied a tension between actual and perceived corruption. Acquitted in 1986, his 2000 trial ended in a controversial conviction after Juror 68, favoring acquittal, was dismissed—leaving the bare minimum needed for conviction under federal law.

To Manuel, it felt like punishment for being too powerful, too close to the people. He warned that when citizens retreat from local politics, corruption fills the void. “The less power people have, the more corruption there’ll be,” or as Edwards said on the ‘83 campaign trail, “When a fella starts telling you how to steal, you better hold your wallet.” Today, there are fewer ramblings about the corruption that dogged Louisiana generations ago. Is that because it’s gone, or because people have ceased to care?

Corruption does not disappear with disengagement. The local kind continues while the corruption that now dominates the public square is distant, bureaucratic, and too complex to directly confront. People have grown fixated on Washington’s scandals while neglecting the affairs of their own parishes and towns. The greater danger, however, lies not in the televised

controversies of national politics but in the quiet erosion of accountability close to home. Louisianians no longer mind their own institutions, they surrender them to apathy and decay.

People are fixated on national media, consumed by distant narratives with little regard for who represents them locally. Few know their police jurors, local legislators, or like Long, their public service commissioners. That familiarity has faded, not simply from indifference, but because the very need for local leadership has diminished. With the exodus of Louisiana citizens courtesy of the so-called “brain drain”, local leaders are no longer strong in the same sway their predecessors

were, and political life has moved elsewhere. The shift of power from Baton Rouge to Washington has hollowed out the connection between citizens and their local institutions. Politics has changed, but so have people.

Today’s shadow of the past

The rich patchwork of distinct cultures and identities that once defined Louisiana and America has been softened by a homogenized popular culture. A voter in Long’s era brought their faith, language, and local loyalties into the voting booth. Today, that voter turns out less and is more a partisan identity shaped by national issues, indistinguishable from someone in Connecticut or California. Those political personalities like the Longs and Edwards who once animated parishes

with charisma are absent and what was once noisy and alive is now muted. “The passion is gone,” Manuel said. “The people are gone. It feels like politics has been drained of life here.”

In 2022, when many of his peers left Mamou for what they hoped were greener pastures, Manuel ran for council. His decision was about loyalty and legacy. “I stayed because of my father,” he said. “He never left Mamou. He believed even in a small town you could make a difference. I wanted to prove that’s still true—I can show that some of us still care.”

The Louisiana State Capitol still towers above Baton Rouge, the tallest in America, a monument to Huey Long’s audacity. But it is also a tombstone, marking the death of an era when local politics was powerful enough to bend Washington to its will. Ninety years later, Louisiana has become a step child to the ghost of FDR, and the parishes that once pulsed with political life have grown quiet – but not silent.

“Local politics began to die with Huey in more ways than one,” Manuel reflected. “But some of us are still here. Some of us still believe our towns matter. That may not be enough to bring the old days back, but it’s enough to keep something alive.”

Huey Long’s voice is gone, but men like Eugene Manuel prove that his lesson endures: populist politics is strongest when rooted in people, in place, and in the belief that the most unsuspecting people in America can still have a chance to shape their destiny.

“God don’t let me die – I still have so much to do..”

Huey Pierce Long

August 30 1893 – Sep 8 1935